BEING IN SWITZERLAND

Nicolas Boldych

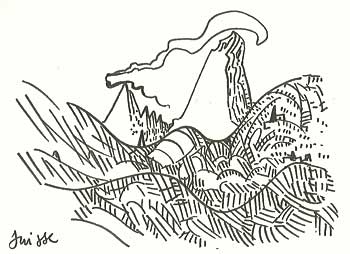

Mont Blanc

On a clear spring day, from the top of the fortress in Grenoble, you can just make out Mont Blanc: a magnet which attracts your attention, an emblem spanning the border between France and Italy. For many years it was a trophy fought over by these two countries, a living legend which changed colour with the seasons: from white, to grey, to blue. You only need to follow the outline of the Belledonne massif and let your gaze travel north, beyond Chambéry, towards Switzerland and the Savoy and you will discern it, or rather, you will be conscious of it. It is almost like a ghost: a white dome rising into the light spring air, dominating the space around it, and taking on for a few minutes a sort of cosmic significance: something we have become unused to. This is the guardian mountain of Geneva, the central point of the system which controls the physical and symbolic separation of France and Italy. On a clear spring day, from the top of the fortress in Grenoble, you can just make out Mont Blanc: a magnet which attracts your attention, an emblem spanning the border between France and Italy. For many years it was a trophy fought over by these two countries, a living legend which changed colour with the seasons: from white, to grey, to blue. You only need to follow the outline of the Belledonne massif and let your gaze travel north, beyond Chambéry, towards Switzerland and the Savoy and you will discern it, or rather, you will be conscious of it. It is almost like a ghost: a white dome rising into the light spring air, dominating the space around it, and taking on for a few minutes a sort of cosmic significance: something we have become unused to. This is the guardian mountain of Geneva, the central point of the system which controls the physical and symbolic separation of France and Italy.

Italy spreads out to the east and south towards the Mediterranean, the islands, the Balkans, as far as Carthiginian Africa and the Libyan coast of Sirte, but what about Switzerland? Switzerland is different because it only leads back to itself: its dizzying heights take you up to the lakes, their final statement, and to ancient pastures such as those in Engadine, as pure as Nordic lands. The cities of Switzerland are like impenetrable fortresses and, once breached, lead you on to the inner regions and to the roof of Europe, their exact opposite. Switzerland is a country with no access to the sea, in the centre of Western Europe: a land of rocks and water.

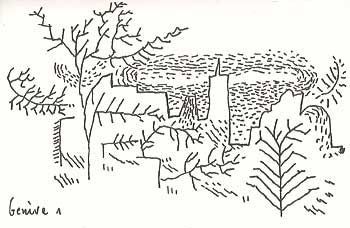

Geneva: an adjustment zone

For the French, Geneva comes as the first of these city-barriers. Arriving from Land of the Dauphin, you can follow the line of Lake Bourget and Lake Annecy, thin ribbons of deep water aligned north to south. These will lead you gradually to the great sea of Lake Geneva, looking like a southern imitation of Lake Constance in Germany. Switzerland welcomes visitors with its great expanses of water. After Annemasse, you come to a sort of natural and political barrier, the only important place in Western Europe where you still run the risk of not being able to pass through customs...You have to file between two customs posts, like passing between two mountains, and then you reach an adjustment zone known as Geneva. For the French, Geneva comes as the first of these city-barriers. Arriving from Land of the Dauphin, you can follow the line of Lake Bourget and Lake Annecy, thin ribbons of deep water aligned north to south. These will lead you gradually to the great sea of Lake Geneva, looking like a southern imitation of Lake Constance in Germany. Switzerland welcomes visitors with its great expanses of water. After Annemasse, you come to a sort of natural and political barrier, the only important place in Western Europe where you still run the risk of not being able to pass through customs...You have to file between two customs posts, like passing between two mountains, and then you reach an adjustment zone known as Geneva.

Geneva can be viewed as the space between two pressure zones: low-pressure France and high-pressure Switzerland. Geneva is the intermediate zone. This is attributable to the influence of Janus or Mercury. This city with two faces, squashed between the Rhone corridor and the Valais, is a place of passage, of flowing water, currencies, men in jackets and ties, businessmen and builders. It's a kind of decompression chamber between France and the Swiss hinterland which can be summed up as a sea developed from a southern fjord. The atmosphere in Geneva is a combination of mountain breezes and sea air.

The Ego-crystal

This prosperous city, with its pressurized but calm atmosphere, is appropriately represented by the symbols of a key and an eagle. Aware of this fact, the French tourist can wander its grey, elegant streets, with their matt appearance and their little low buildings, repeating to himself that he has finally arrived in Switzerland. But just to assure himself of this fact, he only has to glance, slightly intimidated, into the shop windows of the Geneva jewellers and admire their creative work: a distant echo of the Barbarian goldsmiths who brought their craftsmanship from the Eastern Steppes. This originality has no connection with the language, nor is it related to the Calvanist architecture which lends the city a London air: the Baroque style of Savoy is already a distant memory. Nor does it derive from the close proximity of those high mountains, but rather from a deeper source: a sort of religious and philosophical echo. The breadth of this creativity is attributable to the fact that here, in this place, time is not same as elsewhere, even if it can be measured objectively by those famous Swiss clocks you see in every shop. The Swiss originality has its roots in the country's long history, and in its long struggle against Imperial might. This is a history which unfolded in parallel to those events, deliberately avoiding friction and the political power game: the history of a modest but tenacious people. This prosperous city, with its pressurized but calm atmosphere, is appropriately represented by the symbols of a key and an eagle. Aware of this fact, the French tourist can wander its grey, elegant streets, with their matt appearance and their little low buildings, repeating to himself that he has finally arrived in Switzerland. But just to assure himself of this fact, he only has to glance, slightly intimidated, into the shop windows of the Geneva jewellers and admire their creative work: a distant echo of the Barbarian goldsmiths who brought their craftsmanship from the Eastern Steppes. This originality has no connection with the language, nor is it related to the Calvanist architecture which lends the city a London air: the Baroque style of Savoy is already a distant memory. Nor does it derive from the close proximity of those high mountains, but rather from a deeper source: a sort of religious and philosophical echo. The breadth of this creativity is attributable to the fact that here, in this place, time is not same as elsewhere, even if it can be measured objectively by those famous Swiss clocks you see in every shop. The Swiss originality has its roots in the country's long history, and in its long struggle against Imperial might. This is a history which unfolded in parallel to those events, deliberately avoiding friction and the political power game: the history of a modest but tenacious people.

In the centre of this city, which stands on the shores of Lake Geneva, the shop windows display the expensive jewellery destined to be purchased by Norwegian millionaires or Saudi oil magnates. It is here that you can feel the essence of Switzerland: in the expressions of the passers-by, the bank-clerks, and post-office or railway workers. You can see a quiet, closed expression on their faces, and read a comfortable feeling of security, a certain precision and seriousness, in their gestures. It is these qualities which have enabled the Swiss, by means of clever housekeeping and aptly demonstrating the far-sightedness of Alpine-dwellers, to amass enough reserves to tide them over thousands of winters.

Everywhere in the city, on the café terraces or in the bookshops, and in a pervasive atmosphere of calm, you can feel the work of the Swiss people unfolding like a prayer, enabling them to maintain their pivotal, self-sufficient way of life. Gradually, you become aware of a subtle aspect of the Swiss character, an element combining determination and introspection, defined by the great writer, Maurice Chappaz, as the "ego-crystal". It is this same "ego-crystal" that produced the likes of Klee, Walser or Cingria.

Burgundian Barbarism

In a street near the very cathedral where Calvin and Farel spoke of a God only accessible to the individual conscience and of a Mountain to be conquered with exertion, you can find a little crowned statue, standing in the centre of a facade. It is the figure of the heretic Gundobado, the distinguished author of the Gombette law, but now left sadly contemplating the modern masses. This individual stands in curious contrast to the cold clarity of Geneva: a barbarian standing above the crowd and recalling a heroic past: the birth of a culture conquered by the power of the sword. For Switzerland was once a country of warriors and heroes, and the heroism of the Protestant movement, often amounting to true military bravery, is commemorated in the "Wall of the Reformers".

The Burgundians descended on this region from the Rhine valley during the fifth century. They certainly came originally from the Scandinavian countries, and from there they also later travelled to the Rhone valley. The Rhine and the Rhone: two names that recall, in different tongues, the links between the Alps, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean, and their separation by water and language. Allying themselves with the Rhone culture and the Latin tradition, the Burgundians founded the Burgundy, a land of vineyards, combining the Franco-Provençal, Latin and Nordic languages, and stretching down towards Provence like a glacier. Alongside the "ego-crystal" of the Swiss beats a heroic heart, as shown in the fresco by Ferdinando Hodler entitled "The Battle of the Giants". This depicts the Swiss Landesknechten returning from the terrible battle of Marignano (the present Melegnano). They are pensive in their hour of defeat, but still strong and athletic-looking. However, Hodler was also famous for his paintings of "heroic mountains". In Switzerland, the mountains are like armed guards, a natural force which offsets the artificial forces of political power.

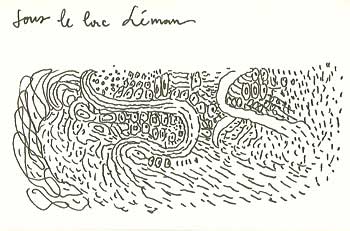

The Goddess Skadi

There are stilt-houses on the lake, whose clear waters reveal a teeming world of aquatic life, as shown in the painting by Konrad Witz: "The Miraculous Fishing". Until the Mediaeval age, many of Geneva's residents lived in houses built on the waters of the Lake, and it was this lake-city of pile-dwellings which confronted the Burgundian invaders, inhabitants of the poor region of Sapaudia. This, on the other hand, was a land of spruce trees, icy waters, and fish-filled lakes. The Burgundians were initially attracted to Lyon and its wealth, lying further westwards, and the capital of the Rhone region. However, the Catholic city of Lyon was not prepared to yield to a tribe of Arian heretics. Perhaps Lake Geneva, surrounded by its mountains, reminded the Burgundians of the landscape and fjords of their native Scandinavia. Paintings by the Swiss artist, Giovanni Giacometti, depict this northern territory of Scandinavia, the land of the goddess Skadi. Switzerland and Norway: two favoured countries for painters of mountain scenery. There are stilt-houses on the lake, whose clear waters reveal a teeming world of aquatic life, as shown in the painting by Konrad Witz: "The Miraculous Fishing". Until the Mediaeval age, many of Geneva's residents lived in houses built on the waters of the Lake, and it was this lake-city of pile-dwellings which confronted the Burgundian invaders, inhabitants of the poor region of Sapaudia. This, on the other hand, was a land of spruce trees, icy waters, and fish-filled lakes. The Burgundians were initially attracted to Lyon and its wealth, lying further westwards, and the capital of the Rhone region. However, the Catholic city of Lyon was not prepared to yield to a tribe of Arian heretics. Perhaps Lake Geneva, surrounded by its mountains, reminded the Burgundians of the landscape and fjords of their native Scandinavia. Paintings by the Swiss artist, Giovanni Giacometti, depict this northern territory of Scandinavia, the land of the goddess Skadi. Switzerland and Norway: two favoured countries for painters of mountain scenery.

In Switzerland, as in Scandinavia, the glaciers wage war on man's activities, driving him backwards and threatening his meagre pastures. In the neighbouring region of Savoy, Mont blanc was long considered a "cursed mountain", especially during the little ice age of the 17th and 18th centuries, when the glaciers spread and swallowed up land which had previously provided fertile pasturage for the Savoy herds. Skadi was married by mistake to Njörd, the god of large feet and of riches, but the couple lived separate lives. Njörd lived next to the sea, surrounded by the cries of gulls, which his wife could not tolerate. Skadi had her home amongst the mountains and glaciers. Njörd and Skadi: the affluence of Lake Geneva, where they also hate the cries of gulls and the impoverished mountains of Vallese. This is another important facet of Switzerland: located at a latitude associated with the astrological sign of Virgo. Wealth, savings, and the cold: when you visit Switzerland, you need to appreciate this combination.

Cosmic Landscape

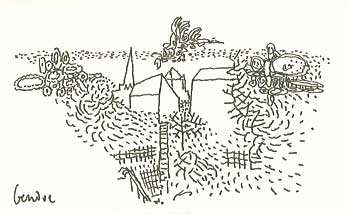

The decompression zone of Geneva always maintains a certain degree of warmth, demonstrated by exotic plants, palms and agaves which beautify the edges of the Lake. As on the Cote d'Azure, water attracts money, and the shores of Lake Geneva are covered with the luxury homes of the rich. The decompression zone of Geneva always maintains a certain degree of warmth, demonstrated by exotic plants, palms and agaves which beautify the edges of the Lake. As on the Cote d'Azure, water attracts money, and the shores of Lake Geneva are covered with the luxury homes of the rich.

Just like Nice, Geneva has all the stately luxury of a cruise ship with its attendant flocks of birds. High-class yachts, water fowl, and crowded ferries: this is the spectrum of modern life presented to a tourist visiting the city.

We have come a long way from the vision of Geneva depicted by Konrad Witz, from a landscape made up of water, earth, rock and sky: silhouettes, colours, and materials collected together and dominated by stately figure of Christ, robed in purple. The only signs of wealth in the picture relate to the fish-filled waters of Lake Geneva and the golden fields discernible in the distance. On the horizon stands the outline of Mont Blanc - the "Cursed Mountain" - whose presence, in a similar way to the fortress at Grenoble, seems to emphasize the cosmic nature of the scene. It is this combination of the cosmic dimension and evangelical indigence that we find in the works of the great writer, Ramuz, especially at the end of "The Life of Samuel Bellet", which depicts the rustic life of fishermen on Lake Geneva. However, you only have to go a short distance from the city, along the coast between Geneva and Lausanne and up into the hills, to rediscover this special feeling of the cosmic dimension, when the mountains seem to rise up from the sea and become a spiritual symbol once again. Then you can escape the Geneva zone of adjustment, after crossing the barrier which takes you to the inner Switzerland. |

NUMBER 11

NUMBER 11

NUMBER 11

NUMBER 11